Ethiopia is a land locked country in North East Africa, borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti and Somalia to the east, Sudan and South Sudan to the west, and Kenya to the south. The country has a diverse climate and landscape, ranging from equatorial rainforest with high rainfall and humidity in the south and southwest, to the Afro-Alpine on the summits of the Simien and Bale Mountains, to desert-like conditions in the north-east, east and south-east lowlands.1 Ethiopia is governed through an ethno-federalist structure and is comprised on ten regions (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Somali, Benshangul-Gumuz, Sidama, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP), Gambela, Harari Peoples) and two City Administrations, Addis Ababa (the capital) and Dire Dawa.1

Ethiopia’s climate is generally divided into three zones: 1) the alpine vegetated cool zones (Dega) with areas over 2,600 meters above sea level, where temperatures range from near freezing to 16°C; 2) the temperate Woina Dega zones, where much of the country’s population is concentrated, in areas between 1,500 and 2,500 meters above sea level where temperatures range between 16°C and 30°C; and 3) the hot Qola zone, which encompasses both tropical and arid regions and has temperatures ranging from 27°C to 50°C.2 Global circulation models predict a 1.7-2.1ºC rise in the mean temperature by 2050, an average rate of 0.28°C per decade, 3.1°C raise by 2060 and rise by 5.1°C in 2090.3 However, precipitation is projected to decrease from an annual average of 2.04 mm/day (1961-1990) to 1.97 mm/day (2070-2099), for accumulative decline in rainfall by 25.5 mm/year.4

Ethiopia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate variability and climate change due to its high dependence on rain-fed agriculture and natural resources, and relatively low adaptive capacity to deal with these expected changes. Agriculture, water, and human health are the most vulnerable sectors with variation across region based on socioeconomic, institutional and environmental conditions in terms of livelihoods, small scale rain-fed subsistence farmers and pastoralists are the most vulnerable. Ethiopia has frequently experienced extreme events like droughts and floods, in addition to rainfall variability and increasing temperature which contribute to adverse impacts to livelihoods. Primary environmental problems are soil erosion, deforestation, recurrent droughts, desertification, land degradation, and loss of biodiversity and wildlife.1

In addition to loss of human life and livestock death, loss of crop productivity and crop varieties, loss strong social cohesion, loss of the traditional knowledge about predicting rainfall and planning the agricultural calendar are some of the non-economic loss due to climate change induce hazards in Ethiopia.5Hydro-electricity supply, the main electricity supply to the country has been weakened by changing river flows and loss of storage capacity due to siltation of dams and reservoirs. Major floods have caused loss of life and property at different times and in different parts of the country almost every five years. One such flood occurs every 5-10 years the recent ones being in the years of – in 1988, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996 and 2006.6 Moreover, such disasters have long-run negative impacts on development by damaging natural capital and infrastructure, undermining economic development, and setting back poverty reduction efforts.7 Climate change induced non-economic Loss and Damage (NELD) considers climate change impacts that are hard to quantify and whose value cannot easily be determined through the market. NELD includes loss of cultural identity, sacred places, human health and lives, material losses of land fertility or biodiversity for people whose livelihoods heavily depend on fertile land and ecosystem services, as well as traditional knowledge of nature and weather patterns, are of great economic value.8 Ecosystem services like access to water is also highly affected by frequent and severe drought and categorized in severe NELD while land (losses of fertile land), Biodiversity (loss of crop variety and herbal medicine), and health (physical and mental health) was categorized in medium NELD.

Ethiopia’s ambition to achieve middle income country status by 2025 rely on the country’s ability to reduce vulnerability of its economy, ecosystems and people from climate hazards and changes Having a policy framework is important, but it is also equally important to have a framework for monitoring the implementation of policies and well-organized institutional framework. The capability to recover from a loss or disaster is usually significantly lower due to a lack of risk transfer schemes (e.g., insurance or social protection programs), limited financeRisk factors like lack of investment in water-related infrastructure, gaps in access to agricultural technology, or lack of health care services, contributed to increasing losses and damage.

Under all warming scenarios and despite strong mitigation and adaptation efforts substantial adverse effects of climate change and its economic and non-economic loss and damage will be felt in Ethiopia. High vulnerability with its low adaptive capacity makes Ethiopia extremely prone to climate change impact and its related loss and damage. climate induced loss and damage are real phenomena in the country affecting ecosystem, lives and livelihoods of million people Ethiopia and livestock’s yearly. Drought and flood are the main climate induced hazards that frequently and severally occurred and caused damages.

It is very important to set legal framework for enforcement of national policy on disaster risk management at federal and regional level. Besides making climate risk analysis an integral part of climate adaptation, strengthening climate risk management, expanding climate risk insurance and networks of social security and addressing permanent loss and damage are important factors to consider in Ethiopia to minimize the current enormous climate induced loss and damage.

-

Addressing The Human Rights Implications Of Climate Change Displacement

Submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the Context of Climate Change “Addressing the human rights implications of climate change displacement including …

-

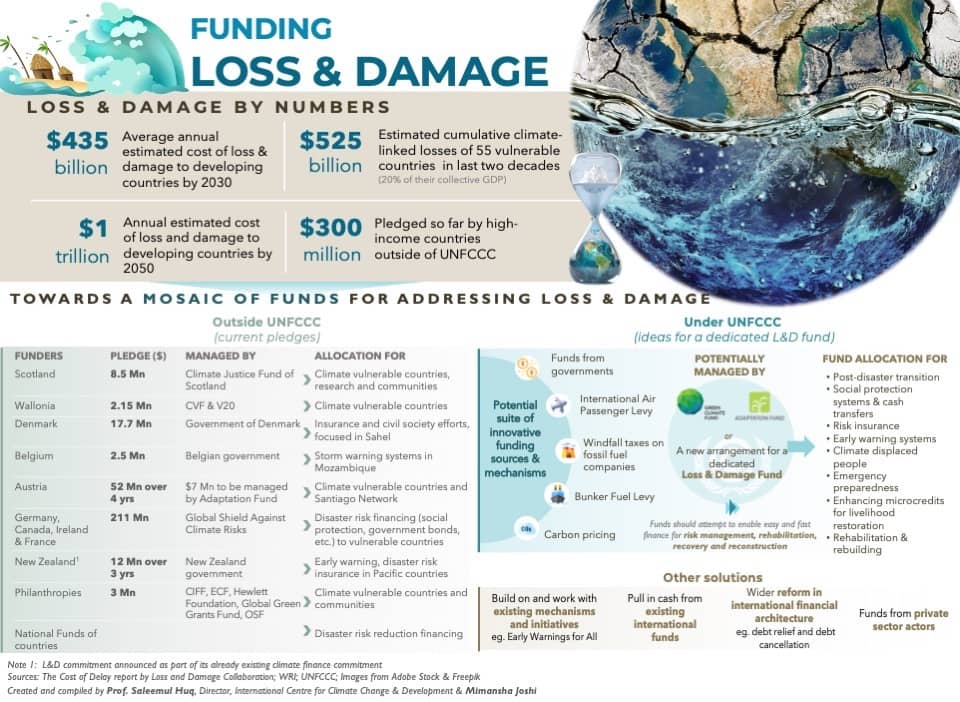

Everything you need to know about the Loss and Damage Fund

The series of extreme weather events in 2022 fuelled by climate change that devastated lives and livelihoods of millions – from the floods in Pakistan and China to droughts in …

-

Ethiopia: Drought is hitting Ethiopia harder than ever

The UN estimates that 4.5 million livestock have so far died due to lack of water and pasture. Millions more are weak and starving. This means traders are unwilling to …